Music for the theatre is one of the three main pillars of Sibelius’ oeuvre alongside symphonic works and solo lied output. Nor did the opera genre leave him unaffected either. In the 1890’s he was overtaken by the same disease which afflicted all the musicians of his time: Wagner fever. In Wagnerian fashion, he would have liked to bring the timeless figures of Finnish mythology onto the stage in the Kalevala-based opera Veneen luominen. The mountains crumbled and a mouse was born: an opera paraphrase in one act, The Maiden in the Tower (1896). Sibelius’ dreams of becoming an opera composer were dashed. We might conclude, however, that composing music for the stage became a panacea for the creative trauma caused by his brush with opera.

Many of Sibelius’ most popular works had their origins in works for the stage. Valse triste was part of his music for Arvid Järnefelt's play Death. Even Finlandia was originally the finale to a musical tableau written for the Press Celebrations 1899. Sibelius continued to write incidental music for the stage and tableaux for the duration of his long creative career. On the one hand, this music reflects his stylistic intentions at any given time and, on the other, one finds a thread running through it connecting these works to the traditions of the theatre music genre in general. The very subject matter of the plays themselves gives rise, at least in part, to the presence of features which otherwise would play no role in Sibelius’ output, a fine example of this being the quasi-oriental exoticism of Belshazzar's Feast (Hjalmar Procopé). As well as Death and Belshazzar's Feast mentioned above, Sibelius’ most important works in the medium are The Lizard (Mikael Lybeck), King Christian II (Adolf Paul), Pelléas and Mélisande (Maurice Maeterlinck), Swanwhite (August Strindberg), Everyman (Hugo von Hoffmansthal) and The Tempest (Shakespeare). His only through-composed stage work besides the opera The Maiden in the Tower was the ‘tragic pantomime’ Scaramouche (Poul Knudsen and T. M.Bloch). Two works – the Karelia Suite and Scènes historiques I – were compiled from music for theatrical tableaux. There are also a number of individual musical items which appeared in stage productions.

Sibelius’ music to Shakespeare's play The Tempest (op. 109) was the composer’s last great musical work for the stage and the jewel in the crown of his work in this genre. In this sense it is a parallel case to the Seventh Symphony, completed in the previous year, and Tapiola, written in the following year, which crown his achievement in the genres of symphony and symphonic poem respectively. As with many of his works, the stimulus to write The Tempest came from a commission. In 1925, Sibelius’ Danish publisher Wilhelm Hansen inquired as to whether he had ever written music for this classic of stage literature. It was probably through Hansen’s influence that the Royal Theatre of Copenhagen turned to Sibelius to commission the music for their unusually lavish production, directed by Adam Poulsen. Sibelius was already a well-known figure in Copenhagen. Only the previous autumn there had been five concerts of his music in the town, which had included the first airings after Stockholm of the Seventh Symphony: they were all sold out.

The first night of the play was scheduled for the autumn, but it was put back to spring 1926, presumably because of the time needed for Sibelius to accomplish such a major compositional project. The composer worked on the score for the whole of the autumn of 1925, the high point of which was the celebration held on December 8th in honour of his sixtieth birthday.

The year of composition of The Tempest is usually said to be 1925, but it is possible that Sibelius continued to work on it during the early part of 1926, since on the 6th January 1926 the Helsinki daily newspaper Helsingin Sanomat reported the visit to Finland of Johannes Poulsen, director of the Royal Theatre. Poulsen commented on his collaboration with Sibelius:

“My wife and I had agreed to meet the composer at a certain hotel outside Helsinki. All three of us stayed there for several weeks while he worked arduously on the score. Sibelius is a hero in the way he throws himself with great seriousness into the task he has taken on. He reminds me of the men in Ensign Ståhl (an epic poem by J. L. Runeberg, ed.). Each morning we conferred as to which scenes should include music, which should include songs or recitatives, etc. – and while we dined we would continue our conversations on these matters. Maestro Höeberg, who is to conduct the music, is most excited about the prospect."

This enthusiastic description cannot refer to the compositional work proper, which took place during the entire previous autumn, but rather the finalising of details as to how the music was to fit the play. In writing the music itself, Sibelius evidently paid fairly precise regard to the wishes of the director. One of Adam Poulsen’s ideas was to replace the shipwreck of the first scene with a musical overture. The curtain would rise just at its climax to reveal a ship being engulfed in the waves. This shipwreck was painted dramatically in Sibelius’ overture. The score contains directions for placing some instruments above the stage, apart from the rest of the orchestra, which was clearly in line with the wishes expressed by the director.

The first night of The Tempest on the 16th March attracted much attention not only in Copenhagen but also in international circles. Reviews noted that “Shakespeare and Sibelius, these two geniuses, have finally found one another”, and praise in particular the part played by the music and stage sets. Sibelius was not present at the performance, a fact quite astounding in itself. Only four days later he set off for an extended European trip to work in Rome on new commissions. His somewhat impulsive agitation towards his Tempest music and other later works can be inferred from the fact that he did not arrive in Copenhagen to see a later performance of the play in spite of the fact that it had been arranged at his specific request. He heard the music for the first time in the autumn of 1927 when the National Theatre in Helsinki staged The Tempest in a production in which his daughter Ruth Snellman played Ariel.

Sibelius’ works for the stage shed interesting light on his attitude towards programmatic music. They also raise the question as to why it was that he never became an opera composer, for there is no doubt that he had a natural gift for theatrical expression. Sibelius had an eye for finding the appropriate musical treatment for a surprising variety of subjects, creating remarkably refined musical portraits of such characters as Mélisande, Swanwhite and the prince, and Prospero and Miranda in The Tempest. By the same token he distanced himself to a certain extent from his subject matter. His music for the stage is not couched in realism, as is film music which follows some particular action or character roles. The music takes its cue from dramatic situations or key personalities, and having done so, it is allowed to develop and work on its own merits. The various musical scenes which Sibelius assembled into concert suites were created as independent musical entities capable of living their own lives. In the final analysis, the question seems to be which is doing the wagging, the tail or the dog? Is the text of the play the governing factor, or the music itself? The dividing line is a thin one and difficult to define. Those works in which the theatrical element has the upper hand and the music is forced into subservience – The Lizard, Everyman, Scaramouche – indirectly bear witness to this non-realist hypothesis. The musical face of these works has a lesser identity per se, and the composer never assembled their music into versions for concert performance.

Sibelius went furthest in revealing his attitude to theatrical music in a letter written to Aino Ackté, dated the 18th October 1914. In it he gave his final word on relinquishing plans for writing an opera based on Juhani Aho's novel Juha:

“According to my thinking, an opera composer of the ‘old school’ could, using this libretto, make a unique virtuosic role out of the figure of Marja. But can one say the same about the others? Juha would have to be silent role. – In the opera style of which I dream, the music should be written first, i.e. absolute music – and the singing – should be the main thing. The text would be coupled to the music, but it must also be subservient in meaning to it. And Juha, in the form in which Aho has created it, is indeed a masterpiece.”

Making the appropriate alterations, the gist of Sibelius’ thinking could also be seen to apply to music for the stage. Once the play has provided the music with a subject and framework, the music is allowed to grow and develop according to its own rules. Shakespeare's Tempest is, of course, a masterpiece, but it was never Sibelius’ in tention to set the words of the play, with the exception of a small number of short sung lines. This left him with the freedom to exercise his imagination, and the play’s magical and poetic atmosphere – with its spirits of the ether, characters of old which appear from nowhere and disappear into thin air, principal characters such as Prospero in his sage-like wisdom and resignation and Miranda with her Mélisande-like tenderness – inspired the composer to find a musical expression to complement these characters, which are just metaphors of human existence – shapes, forms, ideas. The fertile world of The Tempest offered Sibelius an opportunity to dip deeply into the generous melting-pot of his own imagination.

The music to The Tempest comprises thirty-four musical items for soloists, mixed chorus, harmonium and large orchestra (in actual fact there are thirty-five items in all, since item 34a is an alternative epilogue which Sibelius composed for the Helsinki performance). A present-day listener will only be familiar with the overture Op. 109:1 and the seventeen items which the composer arranged into the two orchestral suites Opp. 109:2 and 109:3. When the Tempest music was performed in its entirety at the Savonlinna Opera Festival in 1986, it became apparent that Sibelius had – sad to say – left many interesting items out of his official selections. In 1975, already before this Savonlinna performance, the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra had played twenty-six items in an EBU broadcast concert, and in Sibelius’ 125th anniversary gala concert in 1990, conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste had compiled a suite from twenty-five of the items.

In assembling the suites, Sibelius also made extensive cuts and radically shortened the music. This resulted in the somewhat imbalanced combination in the Intrada-Berceuse (No. 7) of the first suite. The Intrada makes use of chords built on fourths and bitonal harmonic structures and is, alongside the Tempest overture, one of the most daring and dissonant examples of writing in his entire output. It is followed by a warm-toned Berceuse in E-flat minor which seems to be from another world. In the original music for the play, the Intrada is considerably more extended and consequently better argues the case for its own dramatically stark existence.

The Tempest music exemplifies Sibelius’ late style, mature and masterly. As such, however, it does not bear direct comparison with examples of other genre, such as the Seventh Symphony or Tapiola. It is – when all is said and done – a series of minor pieces composed for a specific dramatic purpose. But as a whole it displays an astounding richness of imagination and inventive capacity, added to which it displays features not otherwise present in his later works – not at least drawn to the extent in which they appear here. The music inhabits a wide stylistic area whose identifiable landmarks include expressionism, impressionism and neo-classicism, but succeeds nevertheless in retaining a truly Sibelian stamp throughout. The overture (which corresponds to No. 9, The Storm, in the first orchestral suite) is built almost exclusively around chromatic, dissonant and whole-tone elements which lead to an almost complete absence of tonality. On the whole, modernistic elements, the use of strongly dissonant four note and five-note harmonies, bitonal combinations of chords and dramatic tonal shifts are the stuff of which the Tempest music is made. At the other extreme of the stylistic palette, one finds transparently neo-classical interludes which approach pastiche at times, the prime example of which might be the simple – but freshly countenanced – waltz theme in the Dance of the Nymphs. Even this makes a sudden progression from C major to G sharp minor in a way reminiscent of Prokofiev.

An unusual, almost errant chromaticism characterises both melody and harmony in The Oak Tree, the opening movement of the first suite. Sibelius makes use of whole-tone thematicism and special colouristic effects in the orchestration to depict Caliban's deformed figure and impetuous nature. He paints the figure of Arielin surprisingly dark hues. Ariel's sprite-like, impressionistic nature comes over more clearly in the Naiads movement of the second suite (Ariel's first song in the stage version) which Erik Tawaststjerna has compared with the Sirènes movement of Debussy's Nocturnes. The Chorus of the Winds, the movement which opens the second suite, is also an impressionistic interlude.

In his short, but all the more effective portrait of Prospero, Sibelius lets himself be drawn further into the musical past, as if to emphasise the timeless quality of his sage-like nature. Prospero's music is a baroque pastiche – a rarity in Sibelius' music as a whole – whose extended thematic arch in the Largo recalls Purcell or Handel. Sibelius’ portrayal of Miranda is wistfully tender, as if suspended in reverie. This atmopshere is merely strengthened by having the first violins play its mellow theme four times in all. The decorative figures in the second violins and the syncopated movement in the violas are plaited around the theme like floral garlands in a maiden’s locks. A stark contrast to the serious and tender themes of Prospero and Miranda is formed by other musical items which are linked to the play's brutish and portentous characters and events, where the composer makes use of bare and strident archaisms.

The Tempest was to remain Sibelius’ last music for the stage. The composer’s retreat into silence is even the more enigmatic in the light of this music, which bursts to the brim with musical ideas of great inventiveness and originality, and where even neo-classical ideas are not veiled in the eclectic. For one reason or another, he wanted to write into the suites a "number of small pieces, reallyspiffingly good ones", ditching in the process many possibilities simply crying out to be developed in a lot of the original musical items: think of Tapiola and what Sibelius was able to develop from its modest little theme! Perhaps from Sibelius' viewpoint, the themes of The Tempest did not have the necessary symphonic dimension.

The above-mentioned performances of the Tempest music, either complete or in a form more extensive than the orchestral suites provide, have shown that it is possible to assemble viable alternatives to the composer's suites when full-blooded concert versions of the music are called for. Circumstances made a significant change for the better in 1992 when the complete Tempest music was made available for the first time on disc. This recording was based on the 1927 Helsinki version and was made by the Lahti Symphony Orchestra, the Lahti Opera Chorus and a number of soloists also working out of the town of Lahti. The conductor was Osmo Vänskä.

By making use of the programming possibilities of CD players, a modern listener may try his hand at assembling à la carte versions of the Tempest music. But listening to the music in its entirety is something to be heartily recommended. Although a place has been found for some short and less significant items tied to the dramatic action, many of these have a distinct musical charm of their own. With the text of the play in hand, and Sibelius’ music playing, Shakespeare characters spring to life in the imagination just as Sibelius conjured them forth with his music.

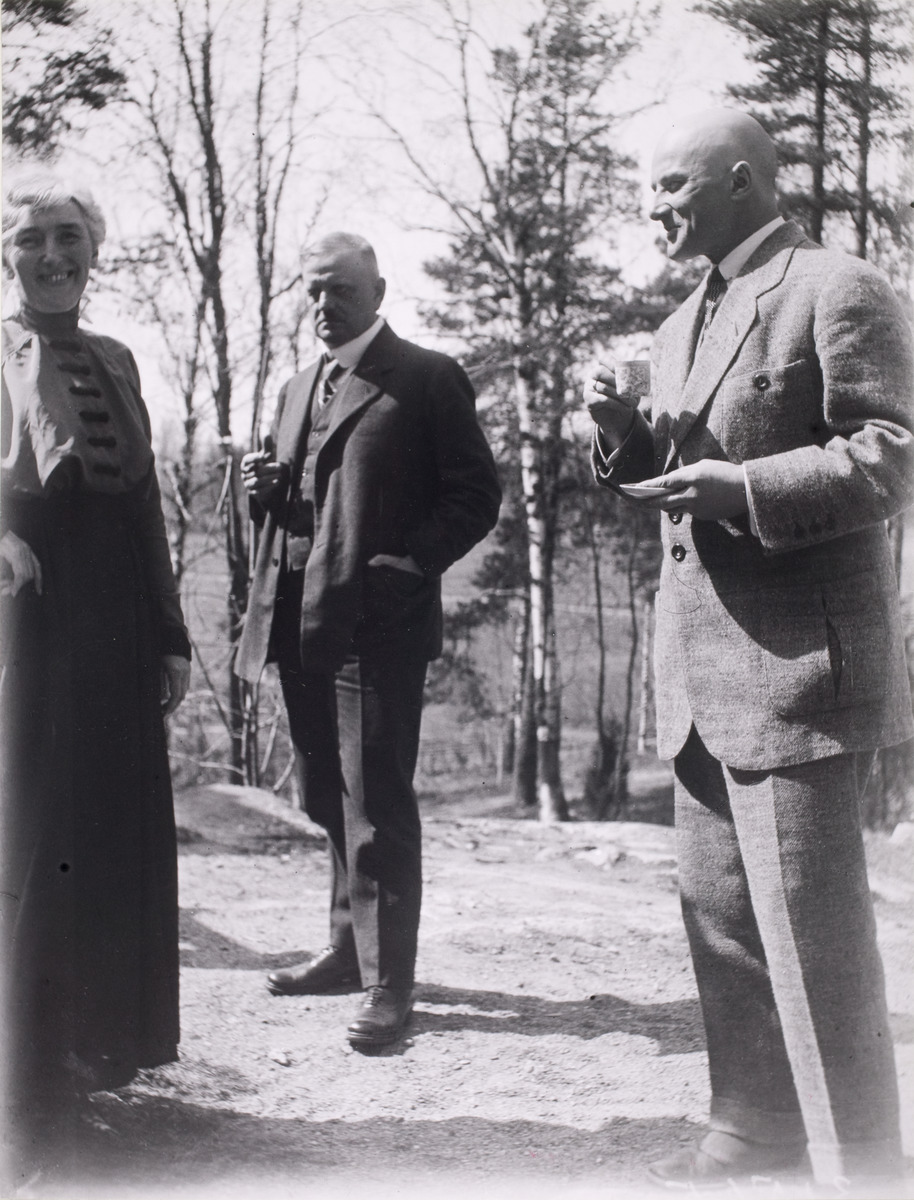

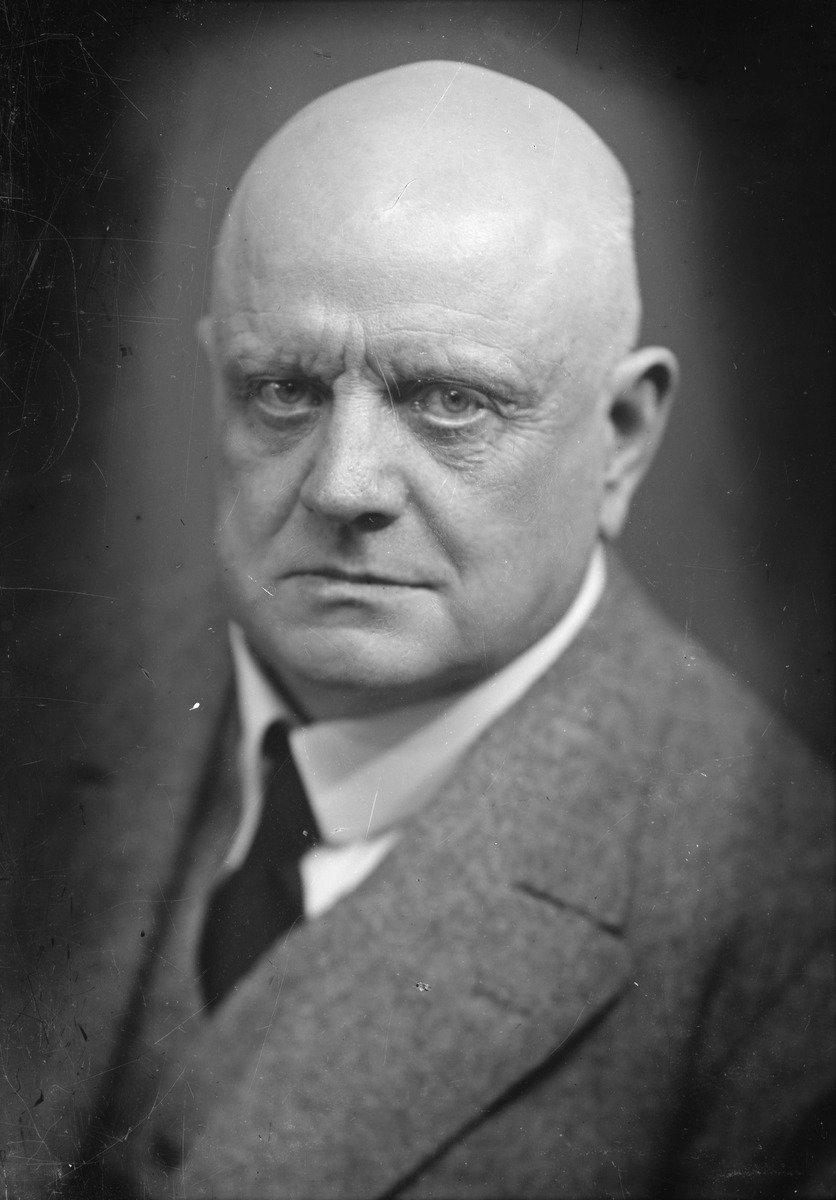

Featured photo: Aino and Jean Sibelius with Adam Poulsen in Ainola in 1924. Photographer unknown. Museovirasto, Historian kuvakokoelma.

Referred recordings:

The Tempest, Op. 109 (complete version, sung in Finnish). Lahti Symphony Orchestra, cond. Osmo Vänskä, with soloists and Lahti Opera Chorus.

BIS CD-581

The Tempest, Op. 109 (complete version, sung in Danish). Monica Groop, Jorma Hynninen, Jorma Silvasti, Raili Viljakainen, Sauli Tiilikainen, Savonlinna Opera Festival Chorus, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, cond. Jukka-Pekka Saraste.

Ondine ODE 813-2