When I arrive at the Alexander Theatre about 10 minutes before the performance begins, the soundscape in the foyer is overwhelming. It is generated by the audience, made up of daycare and school groups. Opera Box’s new children’s opera Kielenvaihtaja (“The Language Shifter”) is about to begin. Taking seats in the auditorium does little to quiet the commotion, but the impact of the first sounds of the performance is immediate. The audience is captivated from the very first second.

Kielenvaihtaja includes immersive, audience-participatory elements that can sometimes feel downright awkward to adult spectators. Today, however, the situation is quite different: every line addressed to the audience is met with a spontaneous and enthusiastic response.

After the performance, I meet Opera Box’s director Ville Salonen, who has just come offstage. In addition to serving as director and singing the tenor role, Salonen is one of the two librettists of Kielenvaihtaja and was also responsible for the visualisations. He leads me to the theatre’s upper foyer, where we find a slightly quieter corner. Downstairs, some daycare groups are still putting on their outdoor clothes, while schoolchildren eat their snacks. The soundscape has returned to a state of joyful chaos.

“In children’s opera projects, touring performances at schools are crucial from the perspective of accessibility and equality,” Salonen says. In the same breath, however, he emphasises the importance of performances like this one in a traditional theatre setting. “Just arriving in the dignified surroundings of the Alexander Theatre, with its large velvet curtains and all that, creates an experience that stays with children. For many, this is their first encounter with opera or theatre.”

The production’s mobility has been carefully considered in the compositional work of Kielenvaihtaja. The three soloists are accompanied by a single violinist. Salonen admits that he was initially somewhat sceptical about whether the concept would work, wondering how a treble instrument could support three singers. These doubts quickly vanished. With the help of a looper, a single violinist is able to create richly layered soundscapes that incorporate rhythmic elements; at times, the violin blends seamlessly into the voices.

Between cultures

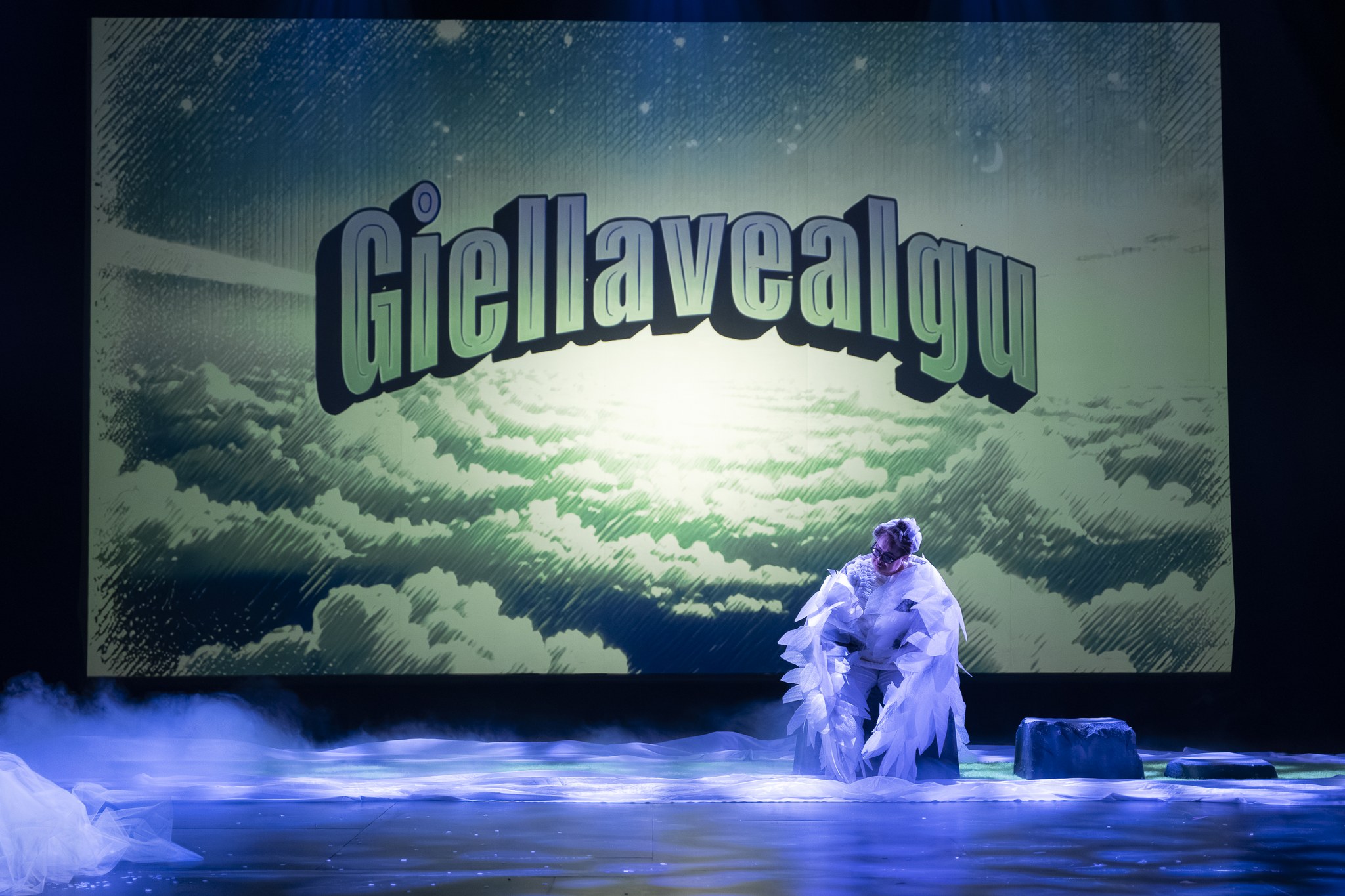

Kielenvaihtaja tells the story of a bluethroat, a northern bird that flies south. Along the way, it learns to imitate the songs of others and switch fluently between languages, but in doing so loses its own language. The opera’s title involves a kind of linguistic wordplay, as the bluethroat’s name in the indigenous Sámi language, Giellavealgu, literally means “language shifter.” Over the course of the opera, the bird reconnects with its lost Sámi language with the help of a snowy owl and an Arctic fox.

I contacted one of the opera’s two composers, Pessi Jouste, by email. They told me that they had reflected extensively on the project’s point of departure, which can easily be interpreted as problematic.

“Perhaps the central musical question for me was this: as a Sámi composer writing music for an opera set in the North, with an entirely Finnish cast of performers, how should one relate to that?” Jouste explains that Sámi musical culture differs from Western musical culture in very fundamental ways. Differences relate to the ontology of music itself – what music is understood to be in the first place.

“Families, lands and certain melodies are intertwined or may even be different manifestations of the same thing. From this perspective, Sámi customs are in some respects at odds with Western musical practices. In particular, ideas associated with European music culture – such as ‘absolute music,’ the separation of art and artist, and the habit of distinguishing ‘art’ from other areas of life – differ fundamentally from Sámi music culture, in which things like music, performers, families, lands, ancestors and events are by default very closely interconnected.”

Jouste says that they resolved this tension by leaning more explicitly on the Western tradition of programmatic music, composing ‘Western music’ that programmatically depicts the North. Jouste describes, for example, the creation of the prologue: “I imagined a certain landscape and playing ‘that’ on the violin, and then I wrote it down. One guiding idea was a sense of softness and a light spatial feeling that surrounds you here in the North, far away from noise and light pollution. I didn’t want to force the music at all, just let it emerge.”

New creators, new audiences

“It’s important to give opportunities to new artists.” This is a theme Salonen returns to repeatedly during the interview. “Opera Box wants to give opportunities to new artists, both composers and singers. It’s important to us that singers are engaged through open auditions and that new composers are given chances to create.”

I sense a quiet critique of programming practices in major opera houses. Salonen confirms my impression but acknowledges that the current market situation is challenging overall. “Audiences seem to want more and more of what is familiar and safe,” he says.

Despite this, Salonen’s tone is anything but pessimistic. “Opera isn’t dying. It’s been around for 500 years, and it will continue to find new forms. But it must always build a new relationship with its audience.” One way of doing this, he suggests, is through contemporary composers and topical themes.

The music of Kielenvaihtaja was created through close collaboration between Jouste and co-composer Elias Nieminen. Jouste describes the partnership as natural, noting that they have previously worked together in Sámi ensembles such as Ulla Pirttijärvi & Ulda and Suōmmkar, as well as in Nieminen’s own group, the Elias Nieminen Ensemble. “There’s a lot of shared musical background, which probably comes through in the aesthetic cohesion of the final result. In practice, we divided the pieces between us, and as the work progressed, we listened to each other’s material, borrowed musical motifs, and so on.”

Jouste describes his relationship to children’s culture as Miyazakian, referring to Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki. “On a musical level, I didn’t think at all about the fact that this is a children’s opera. As a child, I enjoyed both adult and children’s music and I still listen to both today.”

What is the future of children’s opera?

Kielenvaihtaja forms part of Opera Box’s long-term engagement with opera for children. In 2019, the company produced Vickan & Väinö, a children’s opera in Finnish and Swedish, composed by Cecilia Damström. Last year, it participated in Project Butterfly, a joint initiative between three opera houses aimed at reducing the carbon footprint of touring operas. The project was carried out in close collaboration with young people, who selected their favourite composer (Paavo Korpijaakko) from among the winners of a composition competition. The librettists also worked directly with youth groups.

Climate change is another theme addressed in Kielenvaihtaja, a natural choice given that climate change is progressing faster than average in the Sámi region, Sápmi, making its effects particularly significant for its communities. “But the point isn’t for a child to reflect on these issues on that level,” Salonen notes. “Children enjoy watching singing and dancing. Maybe something stays in the back of their minds.”

“A lot of high-quality children’s opera has been created in Finland,” Salonen says. His greatest concern, however, is the increasing difficulty of sustaining long-term work in this field. “Funding has become strongly project-based,” he explains. “That project-based model leads to the erosion of permanent structures.”

This trend is clearly visible in funding for culture aimed at children. As an example, Salonen points to recent funding cuts to Concert Centre Finland (Konserttikeskus), a non-profit association that organises 1,000–1,500 concerts and music workshops annually in schools and daycare centres. Reduced support has forced performance prices to rise, thereby limiting accessibility.

Still, Salonen remains undeterred. At the time of the interview, 15 school performances of Kielenvaihtaja had already been scheduled, with the next ones set to take place in Rauma, on Finland’s west coast.

Kielenvaihtaja – Giellavealgu

Composition: Pessi Jouste and Elias Nieminen

Libretto: Ville Salonen and Isa Kortekangas

Direction: Isa Kortekangas

Visualisation: Ville Salonen

Lighting: Kalle Paasonen

Cast: Maria Ahmed/Heidi Iisalo, Reetta Haavisto, Ville Salonen

Violin: Lotta-Maria Heiskanen

Duration: 35 minutes

Recommended age: 3–12 years

Featured photo Sakari Röyskö.